The ship that brought my parents and sister to the U.S. in the 1960s is on its last voyage.

For years it was mothballed, then simply docked, and now it will be sunk, put to ocean’s pasture as an artificial reef off the coast of Florida. First it stops in Alabama where it will be prepared for burial. The metaphors for me are clanging loudly, and they hurt. I’m losing my parents all over again. I’m losing their story.

Maybe this news is helping me excavate trapped grief. I’ve been sealed inside a vague mourning since my mother’s death last year (and even my father’s death, now almost 6 years ago). I didn’t cry at my mother’s memorial service because I was too busy being one of the planners, too busy shaking hands and fielding complaints about who didn’t get invited to our private service. I was already overwhelmed by the number of guests and can’t imagine having had even more. The whole experience was an eerie separation from myself. Probably the shock, which I think has only begun to wear off in recent weeks. It takes that long to realize all the details of a loss.

This ship’s burial lunges at me with the reminder that my parents are gone. Their story has ended. So has an age of beautiful illusions about this settler colonial nation, this empire that my father came to work for.

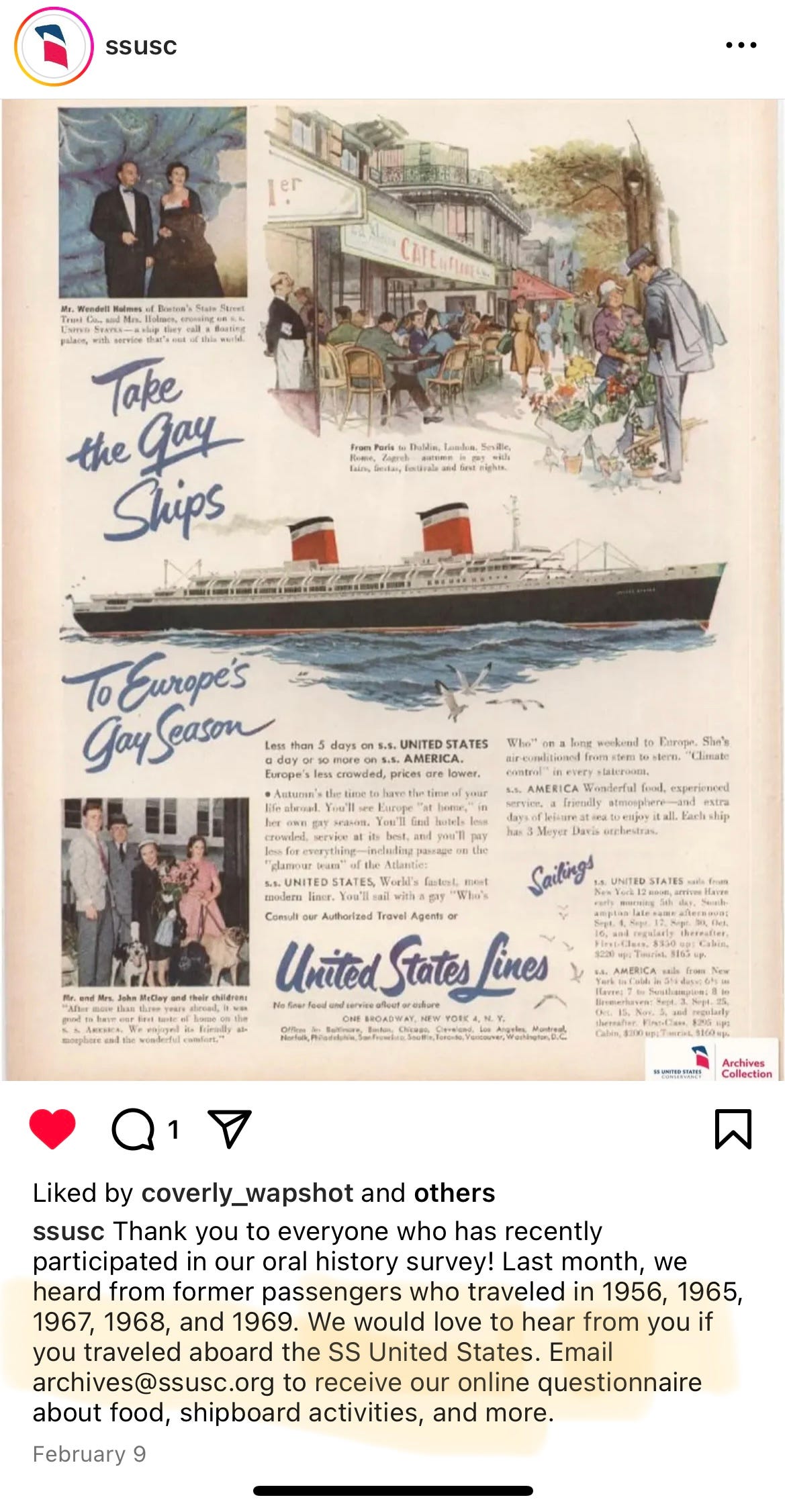

I didn’t know about any of this until last Thursday, when my sister sent me a couple of NY Times articles about the ship’s conservancy efforts, led by Susan Gibbs, and that the efforts to keep the ship afloat had failed. I don’t have a NY Times account (and do not want one) so I can’t add those links, but here is another news outlet that offers video reporting. The lovely conservancy website also has information here. The ship was built with the backup potential to serve as a troop carrier in case of war, which I learned after reading this blog post.

The Pentagon helped pay for the building of the SS United States. This is so incongruous to the ship’s brand I created in my imagination. The bright puffy clouds of innocence I usually see wafting around this ship and my parents on board turns into an eye roll, and an Oh, of course. I mean, why else would the fastest passenger ship even exist? It was designed to defend the empire.

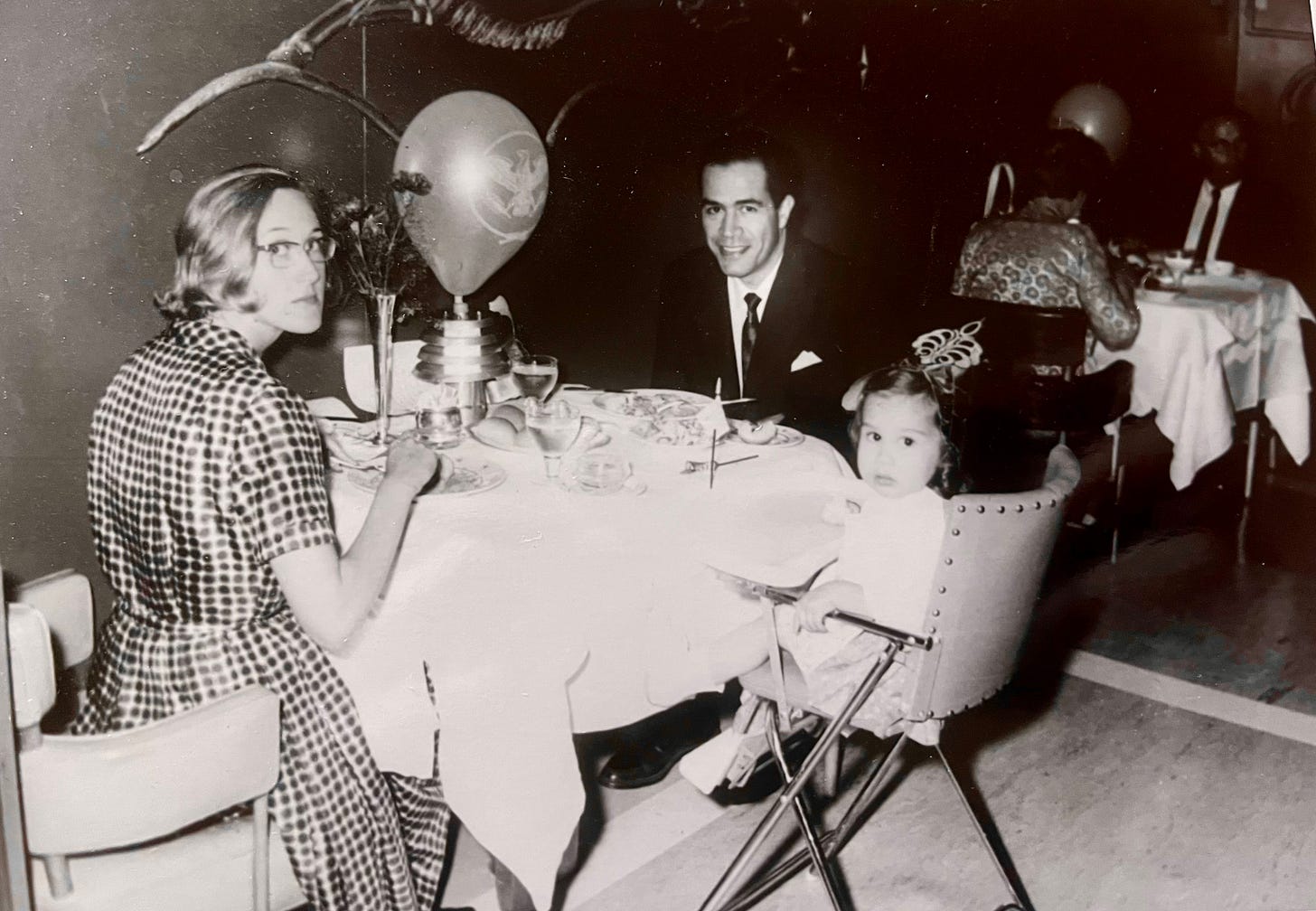

I love and admire that a young couple with a small kid came to the U.S. in the 1960s, because it represented good things and offered a beautiful mirage. Never mind what the (barely) hidden truths were; Vietnam was burning in the background along with whatever other U.S. empiric black ops. But in my parents’ timeline, crossing the Atlantic was a promising new start. My father began his American career helping the empire to design and build weapons. Eventually, such weapons would be used against my relatives in Gaza. My dad followed the industry growth to the West Coast where he worked for the giants, all those names that I now quietly encourage people to boycott and demonstrate against.

Even after tracing and naming that horror and irony, I feel the wildest surge of nostalgia for my parents’ optimism, their sense of adventure. My talent for compartmentalization takes over: I love the artwork from that time period advertising the ship. I love imagining going aboard a vessel the size of the Chrysler building, enjoying the glamour and hype. The amount of energy and trust it took for my parents to make that move astounds me.

My parents are my obsession (I’m not saying it’s healthy). This major point in their story and in my pre-history, this pivotal act when they left and did not turn back, has had reverberations into the very creation of who I am. It’s what my bones are built out of. My birth in a land totally separate from all of our other ancestral lineages began with this ship.

So I look to this ship with mixed feelings, assigning it disparate supernatural powers. I blame it for taking my parents away from my German grandmother. She was the caregiver to my toddler sister, and my grandmother didn’t want them to leave. Then I turn around and plead with the spirit of this ship. I want something from it, benevolent clues or confirmation of my own bright future. How am I doing? Am I on track? Are we there yet?

Do I get a bright future?

My parents were part of an era that lived in that bubble often called the ‘American Dream.’ They thrived for many years on one income and I think their goals for themselves mostly came to fruition. They had the bubble, but I think for much of my life, I was inadvertently bursting that bubble. I rarely experienced the same fantasy country they originally saw or anticipated, and I think it was because of that emotional separation. That distance. All of the sociological ramifications. For all of the benefits and privileges I had, I was missing something essential: connection. There’s probably more things I could list, with investigation.

It does hurt my heart (or my pride?) that I couldn’t deliver a ‘dream come true’ moment for them. My dad wanted an engineer and he didn’t get that; my mom wanted a ballerina and she didn’t get that, either. You know the stereotype of immigrant children, how they’re expected to be successful and are almost scared to do otherwise? I was expected to succeed too, and become an excellent bit of offspring making her parents proud. People generally don’t talk about the kids of immigrants who are the fuck-ups. But there’s a few of us out there. I was a fuck-up.

However, I also feel like I broke free of unrealistic performative expectations, and that too is necessary work. Beneath the veneer, we were a dysfunctional family. I believe being a settler family made that inevitable. There is emotional, spiritual amends and labor involved in changing continents, and my parents did not do that work. It’s okay, they didn’t see the world that way in the 1960s.

But I’m doing that work now.

Maybe if the ship had been named something else, it would feel less harrowing, less like a world-crumbling moment in my family storytelling.

But it’s named after the freaking United States.

As far as metaphors go, does this mean my time is up? Is this the fire alarm saying head to the nearest exit?

This is where my mind goes blank. I don’t know how to answer my own line of questioning.

I still have the dress my mother wore in the photograph of my parents and sister on board. It’s made of silk and has a tear under the left armpit. The sleeves were redone with different material because of sweat stains. The zipper along the side gets stuck. I hang the dress on a door frame, remembering. Probably my mother wore it to the park or the store in my childhood, and I admired the shine and flash of crimson. The pattern still hurts my eyes but it was my mother’s dress, so I interpret that ache as something pleasant. The ship that brought this dress to the United States is sinking. And all of a sudden, I have grown so much older.

Thank you for reading! Thank you and welcome, new subscribers! I am so grateful you’re here!

No big sign-off message today, I’ll start apologizing for feeling nerdy.

**Thank You**